By Sara Muthi

There’s those who see art as an externalisation of the human experience, people who see art as something beautiful or impressive. Some see it as pompous, pretentious and nothing more than an attempt to extract a reaction from the public. Alternatively, there’s those who see art as a branch of academics, who attempt to make connections externally from themselves about the world, politics, art of previous generations and consider it as legitimate a study as history or physics. The “visual academics” is a term I often use.

Personally, I don’t care for art’s aesthetic or emotion. I tend to only share or take seriously educated opinions. That’s just me. Before I respond to any work by an artist, I comb through as much research as I can get my hands on. If possible, interview the artists or curators, plan and re-plan every article and essay, beginning middle and end. Every time. I most importantly refrain from using the word “I”, which makes writing this all the more strange to me. This is a method I developed through my BA, and gives me peace of mind that I am representing every work as objectively as I can, removing the margin of error known I’ve come to know as ignorance. However, I was recently confronted with a performance by Martin O’Brien at the Dublin Live Art Festival that shattered my conventional working methods.

Ample warning was given to the audience prior to entering this performance. Blood, flesh and self harm were the three terms of caution used by the organisers that had instantly tied a knot in my stomach. Nonetheless, as a writer I figured I ought to put my personal reservations aside and attempt to see the work objectively. I was struck by the scent of sanitiser as I reasoned with myself to go up the stairs of the Complex, however I could not force myself into a place of emotional distress for long.

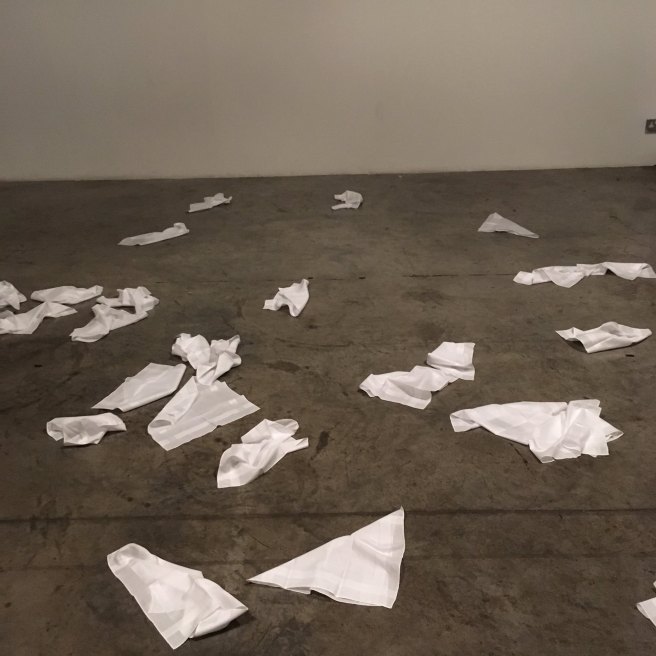

O’Brien slowly makes his way down the stairs into the room, a plastic bag covers his face as he attempts to breath heavily into his stomach. Inhaling deeply and desperately; his ribs become increasingly evident. A tray of surgical equipment occupied the direction the suffocating O’Brien was going. The overwhelming instinct of flight flooded my body, the anticipation of witnessing self harm had already become too much to bare. I quickly and discretely left the room and gasped for air, ironically mimicking the actions of O’Brien.

Part of what makes the work of Martin O’Brien so remarkable is how his work relates to his terminal illness, Cystic Fibrosis. The strain and levels of endurance O’Brien subjects on his body for his durational performances is uniquely tied to the stress his body is constantly in living with C.F. Bob Flanagn is a highly influential performer who also suffered from the same illness and used the endurance of pain within his work as a way of prolonging his life and was subsequently the longest survivor of Cystic Fibrosis, dying at 44. There are no doubt ties between these two practices, however unique in their execution and use of the sick body. O’Brien’s work is highly relevant and influential to today’s performance art landscape and should not be clouded by my own inability to stomach the work.

I cannot express why my body reacted to the way it did to the anticipation surrounding this performance. Guttural is the only word that comes to mind. No doubt there are answers to what prevented me from witnessing an almost fully nude, Cystic Fibrosis suffer from cutting himself. However, I’m not about to go down that road.

At fifteen my art teacher nominated me to shadow a third year sculpture student at the National College of Art and Design. Never had I felt more at home than among artists and academics, all talking about one thing, contemporary art. I hadn’t thought of anything ever since. Nothing could pull my curiosity away from studying the works of Sol LeWitt, Amanda Coogan, Michaël Borremans or the writing of Roland Barthes, Lucy Lippard, Susan Sontag and my person favourite, Peggy Phelan. Now in my MA I am more enthusiast than ever to respond and envelop myself into the contemporary art world, particularly that of the study of performance art. As seriously as I take my work, for most of us, art is not life or death. If you feel challenged by the work of an artist, make it your mission to learn more, be uncomfortable and you will gain so much from it. However, if you simply can’t stomach a work, maybe it’s not for you. At the end of the day, art is just art. There’s art that challenges you and art that’s simply not for you.

Martin O’Brien performed It’s Good to Breath In (This Dublin Air) at the The Complex on 19 August 2017 as part of the Dublin Live Art Festival, curated by Niamh Murphy and Francis Fay. Photographs by Francis Fay.