by Sara Muthi

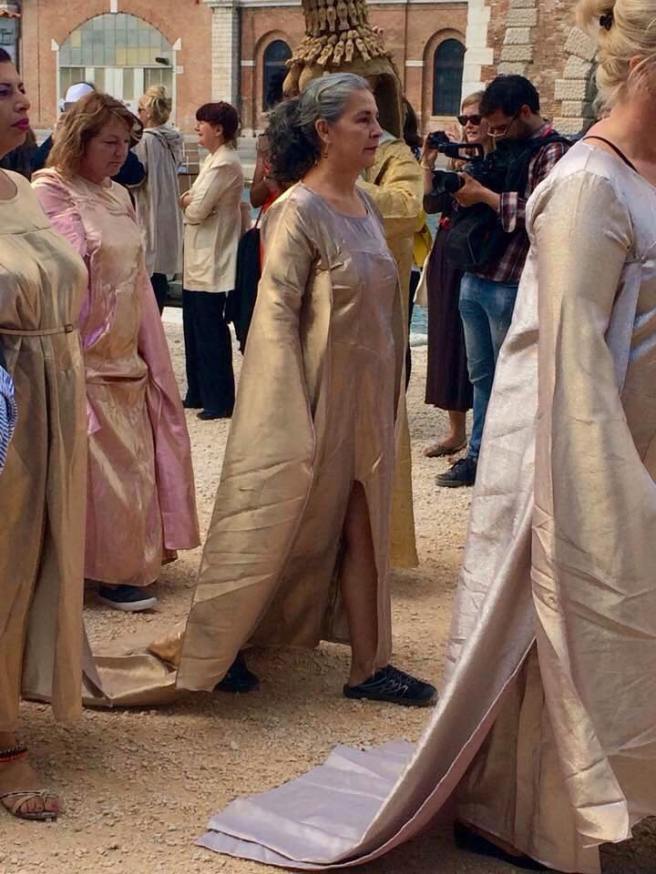

Primarily an all-inclusive singing group formed by Mark Buckeridge, ALL CHOIR aims to use the simple methodology of music to create a space free of elitism and pretension that is all too common within contemporary art today. Creating art that is accessible to a wider audience, an audience who may not have a formal art education, background or understanding is a common target in the artist’s practice. ALL CHOIR is truly a choir for all.

A choir open to people of all ages, ethnicities and vocal ability or professional background; a collaborative community led by Buckeridge and formed around lyrics written by the artist himself. Through multiple rehearsals, this collaboration between the artist and the choir formed the meat of the work. This process leads into a live performance, an intentionally designed booklet containing the lyrics in an almost structural fashion on the page, and a community of people. The process in which the choir was formed was an open call for anyone who wished to participate. This was reflective of the essence of the work: commonality through music.

Lyrics from song Together

In such a communal, almost purely human performance, audience and performer existed on the same plane, no stage or costume was required. There was no separation between singer and spectator. With the intention to break down as many boundaries between audience and performer, the sheet music was handed out to all audience members—some of which sang along, some of which didn’t. There was no pressure, no expectation. The simple vocals of Buckeridge, accompanied by the choir and the audience, created a simple yet powerful aura where all were equal. A sort of minimalist approach to sound echoed through the space, a simple organ complimented the softly ringing sounds of singing voices which wrapped the crowd, creating a most welcoming experience.

All was accessible, no lyric was out of reach of the listeners understanding or experience. There was virtually no difference in the space occupied by singer and spectator, with non-choir people standing directly behind, and beside all choir members, making it increasingly difficult to differentiate between any ‘function’ between any particular people who shared that room.

Lyrics from song All

A large portion of art falls within one of two categories, art that creates dialogue with other art, and art that is in conversation with life. ALL CHOIR is a work which embeds itself into life effortlessly. It does not look like art, it does not act like art, it does not sound like art—it just exists within the realm, without medium or classification, as all mediums and materials were used as tools and did not overwhelm the core message of the work. It did not preach but let itself be open to wonder and astonishment without any moral high ground.

Lyrics from song Together

Its process was not intended to ‘polish’ the work, in which skill and ability would be of high importance; instead, it achieved a multi-diverse choir who simply performed in a gallery. It cultivated a much more instinctive and guttural creation. Even going so far as to providing a sense of comic relief, generating terms such as “tacky entertainment” and impromptu commentary from Buckeridge to the choir.

While the work wasn’t necessarily polished in the sense of musical excellence, it was very well versed and curated. There were particular rhythms and patterns; some of which the choir would sing every other line of a song, or collectively repeat a word for emphasis. These things, while subtle, must have been discussed at length at rehearsal and made for a more pleasant overall experience of the choir.

Lyrics from song Our

This work, with its ambiguous mediums, succeeded not only in creating a more accessible space around art, but also with frustrating the definitions of art. It’s difficult to define a clear relationship between what we know as ‘performance art,’ and this work’s blatant disregard for mediums provides a raw energy, every so much nudging the line between art and life. This a practice which is valuable and necessary in relation to the state of current art practices and exhibitions

Lyrics from song Sweet

A work as subtly human and experiential such as ALL CHOIR can challenge notions of art while simply by being a choir in a gallery; it is fresh and forward thinking. This shall be the type of work that continues to lead the way for the future attitude of medium within performance. A life-like-art which penetrates the social struggles of all members and communally puts at ease all who take part in the space shall be a beginning but certainly not the end for such effective practices. A subtle anthem of warmth, acceptance and perseverance through a simple Choir in a gallery creates a choir for all.

Lyrics from song Struggles

ALL CHOIR, created by Mark Buckeridge and curated by Róisín Bohan, took place on April 29, 2017, at the Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. Photography by Misha Beglin.