by Day Magee

Time is its own language. It is communicated in events, sentences; it’s structure fluctuating, punctuating in a dynamic rhythm.

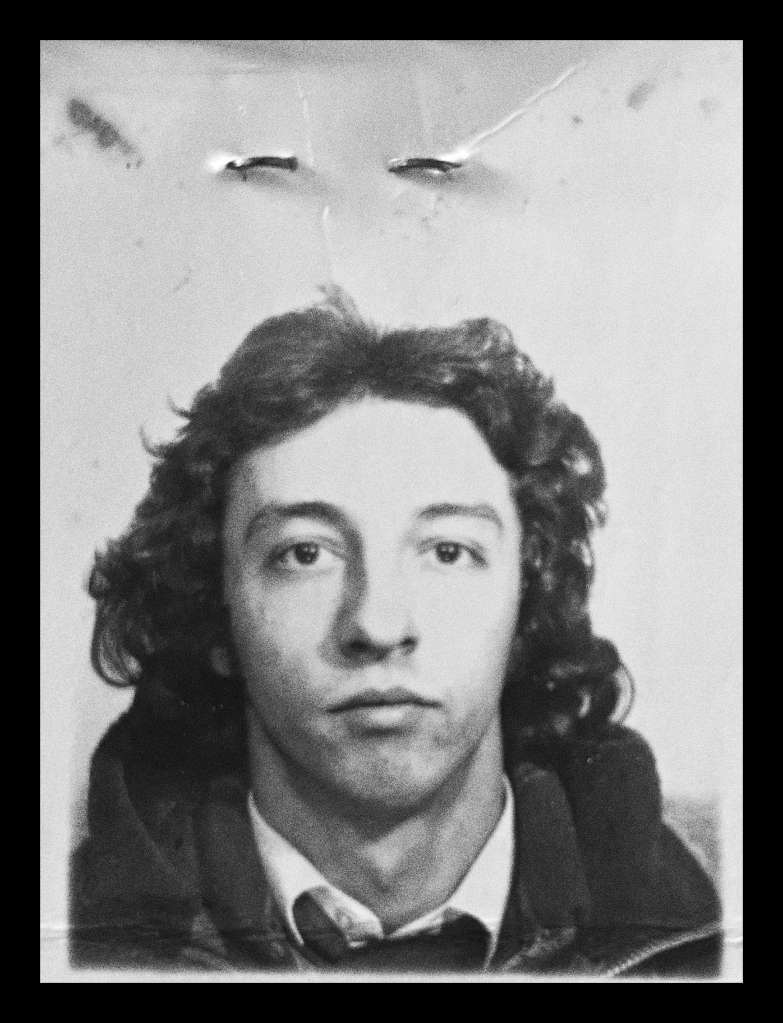

Two and a half years ago, I watched my Father shrivel up from lung cancer, just as his Father before him. I vape as I write this, pushing a little cumulus across the room with the force of breath onto air.

‘Keening’ was a Paganic Gaelic funereal practice, a performance of ecstatic grief in the form of wailing. Often unacquainted with the bereaved, the assigned Keener acted as a proxy for mourners to express their grief vicariously. Historically, the role of the keener was assigned to female, matriarchal figures, lacking perhaps in its cultural mysticism a direct representation of complex male grief.

I’ve never understood myself to be male. I remember the first time my Father caught me sneaking out in girls’ clothes. His face haunts me. I do not however, despite identifying as genderqueer, believe myself to be exempt from male privilege, nor can I have escaped unscathed or unshaped by being raised and socialised as male. One such price was the gift of tears.

What I strangely miss about acute grief is, for a time, how easily I could cry, about anything. Before, I cried maybe every three years. It started mundanely with my Father frustrated and, at the time, on his own looking after two children whilst working grueling shifts as a bus driver. He let rip at some infraction on my part. I was scared, began to cry in earnest, to which he continued to shout “those aren’t real tears – those are crocodile tears!”

(I imagine a crocodile crying the river it waits in.)

And just like that, I couldn’t cry. I became convinced that my own, naturally occurring emotion was my body conspiring so as to manipulate other people. So I trained myself not to. I didn’t cry when I was sexually assaulted multiple times across many years. I didn’t cry when I went through conversion therapy at fourteen to make myself straight. I didn’t cry at the countless older men, for whom I was often The Other Woman, treating me as such. Even when I developed fibromyalgia, I didn’t cry for years.

It was over the course of the first year of grief that I sought to inhabit what non-toxic masculinities I had inherited from my Father.

I recorded, with his permission and enthusiasm, his last breaths. He knew me by then, he even introduced me by my chosen name to his nurses – he knew what I had to do. At that point, we had mutually healed, had come to understand each other beyond our ideologies. In my practice I had become convinced of the magic of performance. A couple of weeks after he died, I fitted a makeshift butterfly net with shards of rose quartz, said to contain feminine energies, playing the recordings from a speaker, and span the net through the sheer air, catching the otherwise masculine sound waves. It was a ritual, as my performances often are, to absorb what remained of him so that grief could begin. And so it did.

I began to keen in the presence of clear quartz crystals, vocally regurgitating what I had absorbed into these objects – death with a life of its own passed back and forth through vectors. The deviant in me thinks of “snowballing” in gay porn. Death and sex are bedfellows in my work. All I knew about sex growing up was that mine was a form of spiritual death, of separation from God. It’s strange, how both “I love you son – does it bother you when I call you son?” and “You can go live with those faggots!” Can be said by the same person and how both can be true.

I performed these five “male” keenings in direct violation of patriarchal suppression. I charged the crystals in a transubstantiating manner over time with the sonic energies of loss. The crystals, carried through successive iterations of the work – each reflecting the first four stages of grief. In 2019, a little over a year since his death, I performed Keening Garden Door in Tulca Festival, whereupon the charged quartz were set like teeth into a door frame. The portal was rooted in a mix of different soils, including some from my father’s grave. I keened a fifth time, before passing through the Door into Acceptance.

Until then, I had tried to orchestrate my own acceptance, in the only way I knew how – to grieve on my own time, alone, and intellectualise it into something to be consumed by other other people whether as art or trying to make other people feel better about my grief. It wasn’t enough just to share it or feel it – it had to be both, simultaneously. And in Keening Garden Door, it was. Multiple people rushed to me after each performance, some sobbing, sharing their own stories of loss, both recent and long ago. The keening was successful, reflected in function now as it had been long ago. Both were true having become real, and both became linked: people coming together in space and time so that they may feel through one another.

It’s strange how, not only in order to process our experience, but in order to realise it, we have to tell a story about it. Words are themselves inert, arbitrary, as perhaps all technologies are, but become charged with intention over time. Something happens, we recognise and speak it – to ourselves or to others – ergo something has happened. These increments link perpetually and acceleratingly until a whole history has proliferated.

I think of myself cuddled into his arms at twenty five years of age in that hospital bed, hating myself for not recording the prayer he spoke over me, because our memory isn’t always enough. And yet, it can also wait for us in hiding, anticipating its own rediscovery.

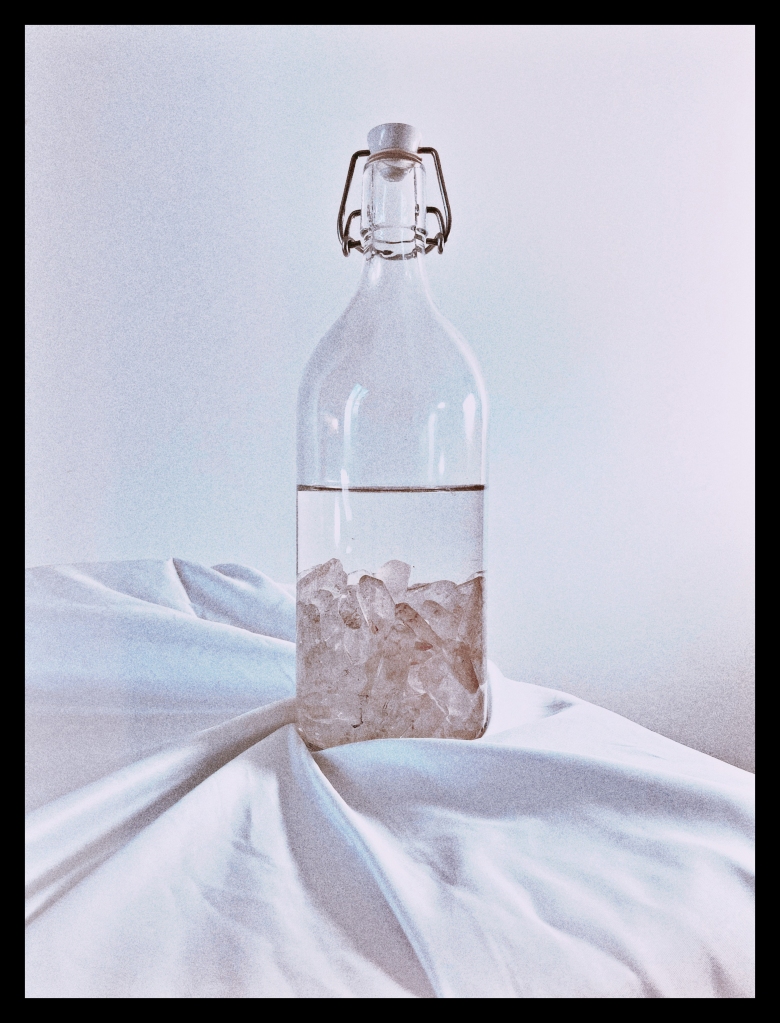

In The Male Keening (vi), I revisit this theme post-COVID, a more collective grief having eclipsed the world as I have wandered in a stupor from my own. The same crystals appear one more time, collected in a glass decanter filled with water, a brew of old grief. I drink from it, and keen again. The image reflects Ganymede the Aquarian, the water bearer, after my own Zodiac sign as I approach my Saturn’s Return, the time in one’s life where everything that has come before must be upheaved. Grief began as this great fog dispersed across everything. Over time, it condensed into various cumulus, more discernible shapes. Now it’s starting to rain. I’m not the same person I was. I mourn who I was as before all this happened as much as I mourn him. I thought I’d have moved towards healing at this point. I have and I haven’t. Grief reveals each moment in time before and since to be its own timeline. Perhaps people are parallel universes, life the intersecting point where they meet, death giving way to new permutations as the facets turn, time the language ting point where they meet, death giving way to new permutations as the facets turn, time the language incrementally communicating these iterations.

I miss you and I love you Dad. I miss the back of your head as you played the guitar at the kitchen table. I miss you gently explaining scripture to me, leaning on the wheelie bin out back with a smoke. I miss you moving your hand through my hair with painstaking delicacy as you prayed for me during my lowest points – we shared the same hospital bed in St Vincent’s A&E, where three years before I had lain, when I had tried to do myself great harm. You had stood over me and could only smile, with no judgement left. I then stood over you, promising to take care of Mom and my brother. Life’s strange poetry continues to riff.

There is a hole in my life, a hole in my understanding of myself and the world. You left me with the tools to love myself. I’ve been sitting for a year staring at them, their applications Greek to me, caught in a slow, barely controlled implosion. What I do remember you saying, in my ear, in those fifteen lucid minutes we had alone together in the chaos of those five awful weeks, was “I bless you son”. And you did. You always had. I hope, one day, when I cross that sea, that I will see you again.